A luminous meditation on art and the act of seeing.

Girl with a Pearl Earring (2003) is not merely a film about a painting—it is a cinematic canvas that reimagines Vermeer’s world through light, texture, and restrained emotion. This curatorial reflection explores the film’s deep visual dialogue with the original artwork, its painterly aesthetic, and the quiet mystery that binds the artist to his subject.

CIACK D'ATELIER

Charlotte Madeleine CASTELLI

7/6/20253 min read

Some films seem to be born from a brushstroke. They skim the surface, evoke, and slowly settle within us and this... in particular, directed with restraint and refinement by Peter Webber, is one of those rare instances in which cinema appears to sculpt with light, shaping each frame as if it were a fragment of a Flemish canvas. It is not merely a visual transposition of a famous painting, but a full immersion into a painterly sensibility that breathes in stillness, suspension, and mystery.

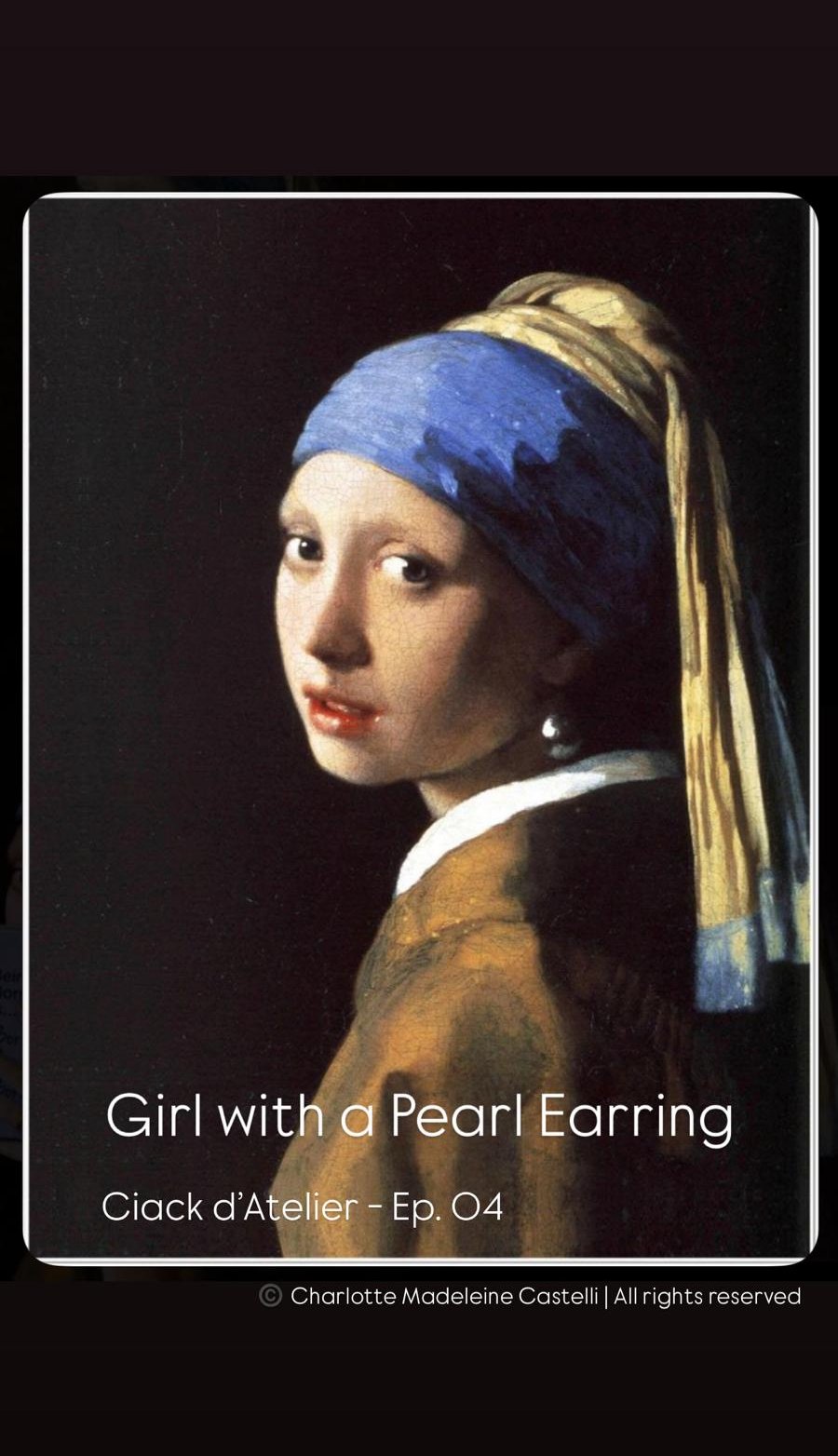

The film draws inspiration from the namesake work by Johannes Vermeer, painted around 1665 and now housed in the Mauritshuis in The Hague. The girl depicted, often called the “Mona Lisa of the North”, has neither a name nor a confirmed identity. It’s not a portrait in the strict sense, but a tronie, a Dutch term used to describe studies of expressions or idealized figures, often in exotic costume. We do not know who the model was, and yet her sideways gaze, her slightly parted lips, and the luminous pearl that catches the light with near-miraculous precision offer us an essence that crosses time and speaks in silence.

Peter Webber, in his cinematic adaptation inspired by Tracy Chevalier’s novel, works like a scenographer of the soul: everything in the film seems carefully composed to recreate the light of Delft, that milky, oblique light Vermeer let in from his left-facing windows, shaping interiors heavy with quiet and layered with daily mystery. The cinematography by Eduardo Serra pays a philological tribute to color and pictorial texture: muted yellows, deep blues, soft and stratified shadows dominate. Surfaces feel alive, fabrics breathe, and time stretches out, like the instant just before a touch.

What strikes me each time I watch it is the film’s ability to suspend time: as if every gesture, a brushstroke, a glance, the faint sound of a brush dipped in oil, carries its own specific weight, a near-sacred density. The gaze of young Griet, played with exceptional subtlety by Scarlett Johansson, is never fully legible. It is the same enigma that lives in the painting: a tension suspended between obedience and longing, between submission and presence, between invisibility and revelation.

Vermeer, we know, painted slowly. Some of his works took months, even years to complete. He used a camera obscura, an optical device that allowed him to capture the behavior of light and space with precision. But his realism was never cold, it was transformative. His domestic interiors are not mere depictions of life, but quiet revelations. The film succeeds in embodying this slowness, this sacred atmosphere, even this emotional attenuation.

The silence between characters becomes musical; what is left unsaid constructs a parallel narrative made of missed caresses, restrained tensions, and unspoken desires.

The connection between Griet and Vermeer is a fictional one, and yet, looking at the painting, I cannot help but believe it. There is an emotional truth in that girl with the turquoise turban, in that mouth that seems about to speak but holds back, something the film captures with a moving delicacy. In a world governed by hierarchy, convention, and silence, that pearl earring swinging like a suspended tear becomes the symbol of a gaze that longs to be seen, of a presence begging to be acknowledged.

Here, art is not simply a source of inspiration, it is the true protagonist. The painter’s studio becomes a place of initiation, a sacred space where pigments are mixed with ancient gestures, and where every color holds a memory, a secret meaning. The moment when Griet grinds lapis lazuli to create the purest blue has always moved me: it’s as if the film were not only trying to restore the face of art, but also its invisible alchemy.

In that gesture, and in the silence that envelops it, I saw a metaphor for artistic creation itself: slow, quiet, devoted. And I thought that perhaps the true heart of this film lies not in the impossible love story, nor in the painting itself, but in the act of seeing. This work compels us to truly see, analytically, contemplatively, to slow down and feel the weight of the images that pass through us.

Through its profound dialogue with painting, this film becomes a work of art in its own right. It does not quote, it does not imitate, it reinvents. And in doing so, it opens up a space for reflection.

But when we look into the eyes of a painted face, are we really seeing the other... or are we always searching for ourselves?

© Charlotte Madeleine Castelli | All rights reserved