Art Beyond Sight

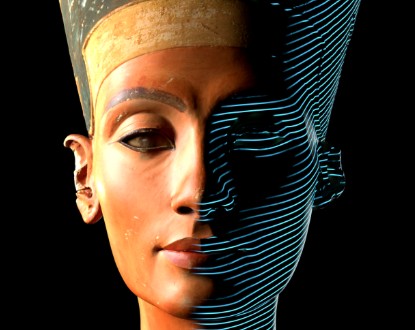

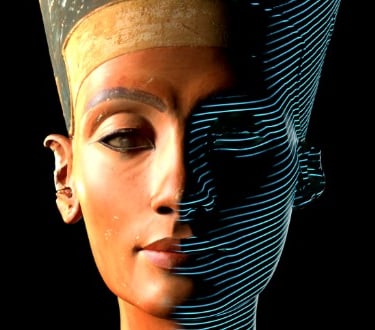

Discover how artificial intelligence is reshaping art for blind and visually impaired audiences. From masterpieces transformed into immersive soundscapes to tactile and interactive experiences, explore a world where you can see with your ears and touch with your imagination. Art is no longer just for the eye—it’s a fully multisensory journey waiting to be explored.

TODAY'S HEADLINER

Charlotte Madeleine CASTELLI

8/23/20254 min read

Seeing with Ears, Touching with Imagination

Art has long been considered a realm reserved for the eye. Paintings, sculptures, and installations were traditionally conceived for visual perception, and accessibility was often reduced to translating visual cues into simplified verbal or tactile forms. Today, however, the advent of artificial intelligence is radically redefining how art can be experienced, opening unprecedented avenues for blind and visually impaired audiences. AI is transforming both the creative process and the consumption of art, creating possibilities that extend far beyond the visual spectrum.

This transformation is not merely about translating images into words or tactile forms. It is about reimagining the artwork itself as a multisensory experience. Modern AI systems can generate descriptions, auditory translations, and interactive narratives that are personalized to the user’s cognitive and sensory profile. Accessibility becomes adaptive, responsive, and deeply situated within the individual experience.

In recent years, artists with visual impairments have pioneered projects that leverage AI to create works designed specifically for multisensory engagement. One of the most emblematic initiatives is Sound of a Masterpiece, a collaboration involving composer Bobby Goulder, Dolby, and the Royal National Institute of Blind People. Through the immersive power of Dolby Atmos technology, iconic artworks—including the Mona Lisa, Munch’s The Scream, and Monet’s Japanese Bridge—are translated into soundscapes that convey color, form, and emotion through auditory experience. Listeners do not simply hear the artwork; they perceive it, inhabiting the space and rhythm of the original visual composition.

The underlying principle is profound: to “see with the ears” is to engage perception beyond conventional vision. Sound becomes a medium capable of conveying texture, depth, and spatial relationships, while rhythm and tonal variation evoke emotional resonance comparable to that of visual engagement. In this sense, auditory experiences are not mere substitutes for vision but autonomous artistic expressions in their own right.

AI also enables deep collaboration between humans and machines, creating new forms of co-creation. Artist Cosmo Wenman, for example, has developed projects in which verbal descriptions and imaginative prompts are processed by AI systems such as Midjourney, generating images that are subsequently transformed into tactile reliefs or narrated sonically. These projects collapse traditional hierarchies between artist and audience, enabling participants—both blind and sighted—to engage in a shared creative dialogue that is simultaneously conceptual, tactile, and auditory.

Other artists, such as Alecia Neo, have explored multisensory installations that, while not directly AI-generated, incorporate technologies that translate visual stimuli into immersive tactile or sound-based experiences. In such works, technology functions as a mediator, enabling participants to perceive narratives, gestures, and environments through multiple channels. AI, in this context, amplifies the possibilities for inclusion, becoming not only a tool but a partner in the creative process.

Practical applications are already transforming accessibility in everyday encounters with art. Tools like Be My AI, integrated into assistive apps, allow users to photograph an artwork or book page and receive detailed, interactive descriptions. The system can identify colors, compositional structures, subjects, and stylistic nuances, while also engaging in dialogue: users can ask questions, explore historical context, or request elaboration on emotional or aesthetic qualities. For artists with visual impairments, such tools are also creative companions, offering feedback and suggestions, facilitating independent experimentation, and expanding participation in cultural discourse.

In Italy, initiatives such as Parts, developed within the Apple Foundation Program at the University of Suor Orsola Benincasa in Naples and further explored by students at the Apple Developer Academy in San Giovanni a Teduccio, demonstrate the potential of AI-enhanced interaction. The system segments artworks into meaningful components—gestures, symbols, figures—which users explore through touchscreens. Each segment conveys a fragment of the narrative, transforming the participant into an active explorer of meaning, rather than a passive observer. Similarly, the Brescia-based app Multiart converts images into musical compositions, linking pixels to piano notes and generating melodies that correspond to stylistic elements, from classical to jazz to rock. These innovations allow users to “hear” the artwork, turning visual aesthetics into a dynamic auditory landscape.

Museums are increasingly integrating AI into accessibility programs. The Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, for example, has launched an automated system that generates detailed descriptions of hundreds of artworks in its collection. The AI provides rich, nuanced insights, including visual elements, historical context, and stylistic interpretation, making masterpieces accessible to blind and visually impaired visitors. These developments highlight a broader cultural shift: accessibility is no longer an ancillary concern but a core element of artistic and curatorial practice.

Yet, technology alone is not sufficient. As Roberta Presta has emphasized in her research on human-computer interaction, AI must be taught to convey nuance, context, and depth. Curators, art historians, educators, and storytellers remain essential, guiding AI to produce narratives that are both accurate and emotionally resonant. The true power of AI lies in its capacity to mediate dialogue between artwork and audience: it is not a replacement for perception but an amplifier, capable of responding to the unique questions and curiosities that arise in each encounter.

The implications extend beyond disability. Multisensory engagement, AI-assisted interpretation, and interactive narration suggest a future in which art is fully experiential, transcending the limits of the eye. Perception becomes distributed across senses, creating rich, immersive encounters where imagination, touch, sound, and cognition converge. In this expanded understanding, the artwork is not confined to sight but is activated through engagement, inviting all participants—regardless of ability—to explore, interpret, and co-create.

In the evolving dialogue between art and technology, the challenge is not only to provide access but to cultivate an aesthetic ecosystem where every sense contributes to meaning. Here, AI is not simply a tool; it is a collaborator, a translator, and a medium for discovery, capable of extending the very definition of artistic experience. In embracing this potential, the art world moves toward a vision of true inclusivity: a culture where perception, creativity, and imagination are shared, dynamic, and limitless.

© Charlotte Madeleine Castelli | All rights reserved