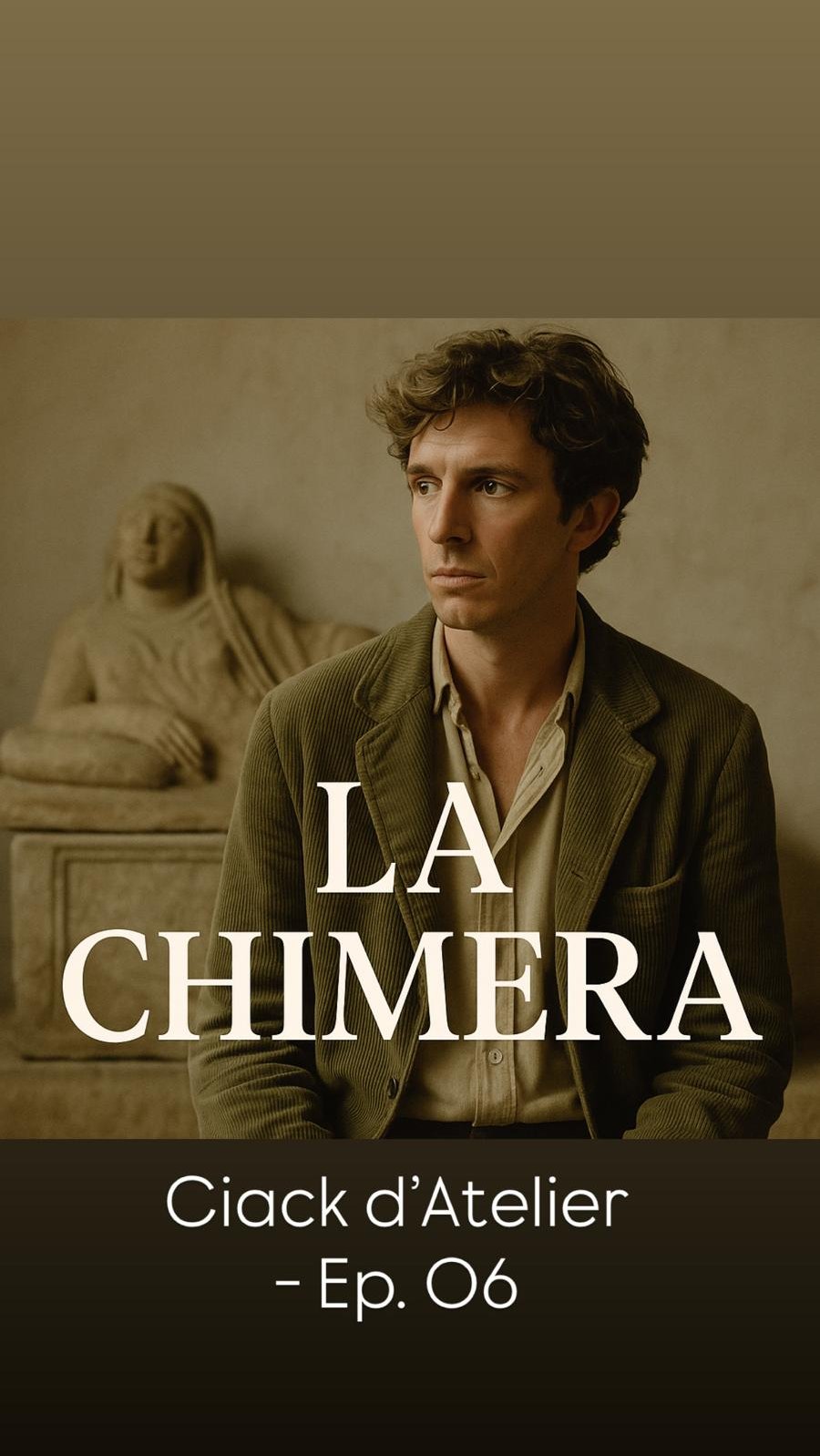

La Chimera

A poetic journey through La Chimera by Alice Rohrwacher, where ancient tombs and lost love intertwine with a deep reflection on the ethics of collecting. Between memory, identity, and cultural heritage, this Ciack d’Atelier explores how contemporary practices—like those envisioned by Future—are reshaping the very meaning of legacy in the digital age.

CIACK D'ATELIER

Charlotte Madeleine CASTELLI

7/20/20253 min read

Collecting the Invisible: Ethics, Memory, and New Forms of Heritage

In the heart of Tuscany, among its wondrous landscapes suspended between enchantment and oblivion, we meet Arthur, an English archaeologist with disheveled hair and an uncertain gait, portrayed with poignant fragility by Josh O’Connor. He is the protagonist of La Chimera (2023), a film by Alice Rohrwacher, an evocative and layered work that digs deep into both the earth and the human soul. This is not a film about collecting in the traditional sense, but about the ancient desire to hold on to what inevitably slips away: the past, love, identity, memory.

Arthur is part of a group of tomb raiders who plunder Etruscan necropolises to sell ancient artifacts on the black market to private collectors. But unlike his companions, he is not driven by greed—his actions are guided by an inner tension, almost mystical in nature, an existential urgency that compels him to search beneath the earth for traces of something lost. He is not after objects, but presences—in particular, that of Beniamina, a woman he loved and lost, who hovers over the film like a mythical figure: unreachable, unforgettable.

One of the most powerful and revealing scenes unfolds when Arthur visits Beniamina’s mother, Flora, played with luminous depth by Isabella Rossellini. Flora lives in a timeless house, filled with memories, worn clothes, and faded portraits. This is where the film unveils its core: Flora owns nothing, yet she preserves everything. Her home is not a museum, but an emotional archive—every object has a soul, every item is linked to a story.

“Not everything that’s buried needs to be unearthed,” her gaze seems to whisper. In this quiet gesture of care, the film outlines an alternative ethics of collecting: no longer accumulation as possession, but rather, attention, resonance, and relationship.

“The past is not something to be bought, nor locked in a glass case. The past must be crossed, welcomed. And sometimes, let go.”

Rohrwacher crafts a critique that is both gentle and incisive of traditional collecting practices—those rooted in rarity, appropriation, and exclusion. Every looted artifact is severed from its origin, stripped of its context, condemned to a silent existence. The film does not moralize, but rather confronts us with essential questions we must ask ourselves as professionals:

Who has the right to preserve memory? And at what cost?

Arthur is a tragic figure: he possesses a gift—the ability to sense the presence of objects underground, as if he could hear memory vibrating beneath the soil. But this gift isolates him, condemning him to an eternal return to tombs and ruins. He is a seeker of chimeras, of illusions that disintegrate between his fingers. His journey is not only geographic but spiritual—a desperate attempt to reconstruct an identity within the cracks of History.

It is within this tension that a vital reflection emerges: What does it mean to collect today? Contemporary collecting is gradually moving away from a pure obsession with physical artifacts, shifting instead toward a broader, more fluid, experiential and shared idea of heritage.

Digital culture has introduced new dynamics: participatory archives, immaterial architectures, distributed and open-access collections. Technology is not an end in itself, but a tool, a means of giving voice to the margins, amplifying memories that have long remained unheard.

It is precisely from this perspective that the Future project takes shape and evolves, with The Heritage as its conceptual and operational cornerstone. For us, heritage is not the result of exclusive selection, it is living material, capable of being reworked and reactivated through innovation.

We do not simply collect artworks, but also industrial memory, narratives, residues of post-industrial landscapes, transformed into accessible, multidisciplinary languages. Technology becomes a vehicle to democratize access, to return meaning and function to what once appeared inert.

La Chimera offers no easy answers. Like the myth it draws from, the film is elusive, ambiguous, at times achingly beautiful. But it is precisely in this ambiguity that it challenges what we often take for granted: our urge to preserve, our assumptions about what is worth saving.

Arthur seeks, digs, listens. But what he finds is never what he expects.

And just like him, we too are called to redefine what it means to transmit, conserve, collect in our time. Future embraces this challenge not by looking backward, but by moving forward—transforming collecting into an ethical, collective, immersive gesture.

Because collecting is no longer about owning rare objects, but about forging meaningful connections between scattered histories, and making cultural heritage something to be lived, not simply observed.

© Charlotte Madeleine Castelli | All rights reserved