Self-Destructive Art

When art chooses its own death, it ceases to be an object and becomes an event, a fracture in time that exposes the fragility of our desire for permanence.

BOOK ON MY TABLE

Charlotte Madeleine CASTELLI

9/22/20253 min read

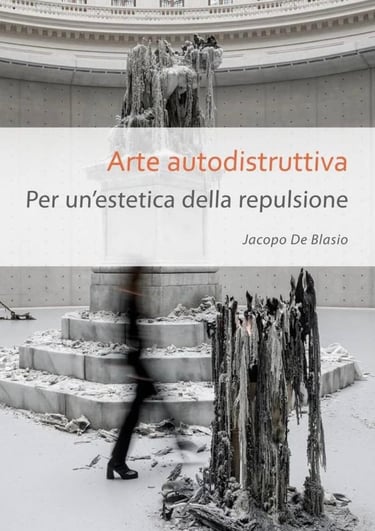

Jacopo De Blasio’s Arte autodistruttiva. Per un’estetica della repulsione (ISBN 9788874903962), published by Postmedia Books in 2024, stands as a rare and necessary contribution to the contemporary debate, for it addresses a dimension that has always unsettled the history of art: the moment in which destruction is not an accident or a misfortune, but the very grammar of the work, the secret structure of its becoming and its inevitable destiny. With a prose that is rigorous yet never heavy, De Blasio weaves a complex map that connects artistic genealogies, manifestos, and philosophical reflections, showing how dissolution is not simply a matter of scandal or avant-garde theatricality, but an aesthetic and political logic that runs across the twentieth century and reaches into the present, where protest and activism turn the museum into a stage for new forms of iconoclasm. At the center of this narrative stands Gustav Metzger, whose manifesto of auto-destructive art envisioned works designed to incorporate their own ending: canvases corroded by acid, plastics programmed to decompose, materials engineered to collapse. In Metzger’s hands, destruction became both material and metaphor, an act that exposed the traumas of war, the nuclear threat, and the alienation of industrial society. For De Blasio, Metzger is not merely a pioneer, but a reminder that fragility itself can become an instrument of critique.

From there, the book moves through Jean Tinguely’s ephemeral machines, created to fall apart in front of the public, and through the rituals of body art, where the artist’s own body becomes surface, wound, and temporary sculpture. Each example is treated not as anecdote but as fragment of a larger discourse that interweaves aesthetics, ethics, and politics. Here the notion of “repulsion,” which De Blasio elevates as the core of his lexicon, acquires its full weight: not simply the feeling of aversion, but an aesthetic device that forces the spectator to confront loss, discomfort, even pain, without the consolation of permanence. Repulsion becomes a key through which to interpret gestures ranging from iconoclasm to ritual vandalism to contemporary climate activism, in which the threat of damage to masterpieces is deployed to draw attention to ecological crisis. In such cases, De Blasio notes, self-destruction is always ambivalent: at once a political and poetic gesture that unmasks dominant ideologies, and a risk of sliding into pure spectacle, where ruin becomes commodity and virality substitutes for critical depth.

The strength of the book lies in holding this tension open. Self-destructive art destabilizes the very foundations of aesthetics: it undermines the fetish of preservation, the rhetoric of heritage as untouchable, the comfort of the museum as temple. The work that destroys itself ceases to be a collectible object and becomes instead a process, an event, a temporality to be shared. It offers itself as an unrepeatable experience, which can be remembered and documented but never possessed. This brings curatorial responsibility to the fore: exhibiting self-destructive works means confronting ethical and political decisions, deciding how to display loss without trivializing it, how to mediate between risk and protection, how to accompany the public through a destabilizing encounter without reducing it to sterile provocation.

De Blasio’s essay insists on this delicate threshold: destruction as language that demands respect and valorization, but also as practice that must be interrogated to avoid being absorbed by the market or neutralized by institutions. In this sense, Arte autodistruttiva is more than a historical reconstruction or a theoretical meditation: it is an implicit manual for curators, an invitation to imagine new forms of exhibition that can accommodate temporality, fragility, and disappearance without betraying their critical force. The exhibition space, in this vision, is no longer a sanctuary for the eternal object, but a transparent device where fragility itself becomes visible and where each curatorial decision is part of an ethical dialogue with the spectator. Ultimately, the greatness of De Blasio’s book lies in its ability to illuminate the contradiction without resolving it, showing how art can find its most radical force precisely in the moment of its self-consumption. In that dissolution a paradox emerges: the artwork that destroys itself, precisely because it is destined not to endure, speaks to us with greater intensity about our own condition, reminding us that all forms are transitory and that beauty lies not in possession but in the fleeting intensity of experience, which strikes us and leaves us, inevitably, alone before time.

© Charlotte Madeleine Castelli | All rights reserved