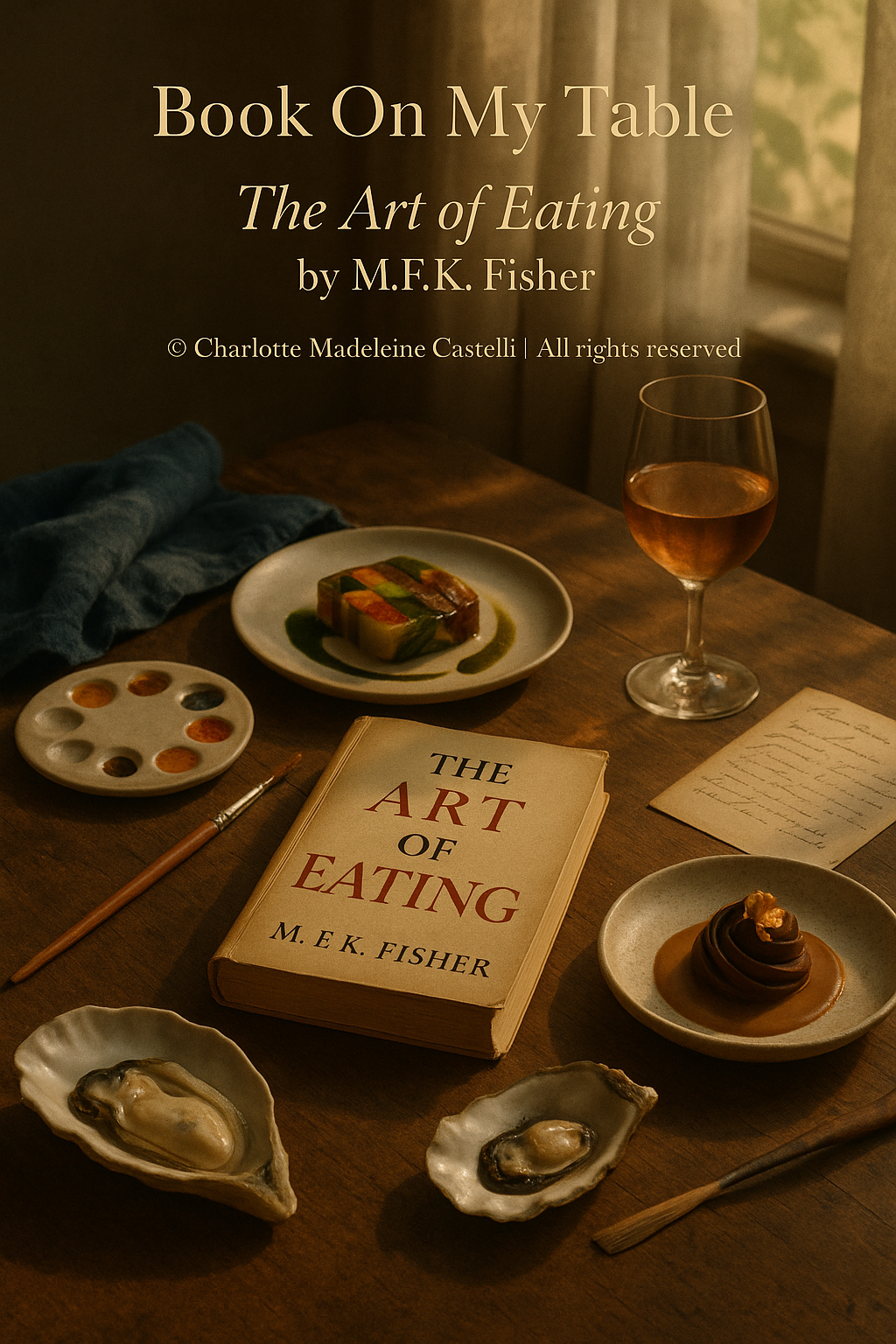

The Art of Eating by M.F.K. Fisher

A literary feast that transcends recipes, The Art of Eating by M.F.K. Fisher explores food as memory, intimacy, and quiet resistance. Through sensual prose and timeless reflections, Fisher teaches us that eating is not just a necessity—but an art form, a philosophy, and a way to feel deeply alive.

BOOK ON MY TABLE

Charlotte Madeleine CASTELLI

7/4/20253 min read

“It seems to me that our three basic needs, for food and security and love,

are so mixed and mingled and entwined that we cannot straightly think of one without the other.”

— M.F.K. Fisher

There is an art that is not taught in academies, nor sealed behind glass in museums. It is a quiet, invisible art that pulses through everyday life—the way one sets the table even when dining alone, the slow, careful pour of olive oil, the attentive listening to someone else’s hunger. It is an art made of hands that knead, eyes that taste before the mouth, silences infused with the scent of toasted bread.

And if this form of art had a voice, it would be that of Mary Frances Kennedy Fisher—soft and learned, wry and ruthlessly honest, as only true sensitivity can be.

This is more than a book: it is a sensory constellation, a living literary organism that breathes and grows within the reader. Composed of five luminous works—Serve it Forth, Consider the Oyster, How to Cook a Wolf, The Gastronomical Me, and An Alphabet for Gourmets—it unfolds like the movements of a symphony. And as in any great symphony, each movement carries its own mood, emotional temperature, and lingering flavor—one that rests on the tongue long after the final note has faded. In her most celebrated collection, Fisher does not teach us how to cook. She teaches us how to live through food.

In Serve it Forth, she takes us by the hand and tells the story of eating as a primal rite—an inheritance from the first man who sat before the first fire.

In Consider the Oyster, she muses on the ambiguity of pleasure, the mystery of texture, the metaphysics of a creature that resists all definition.

But it is in How to Cook a Wolf that Fisher reaches her poetic and political zenith. Written at the height of World War II, in a world of rationing and want, it becomes a manual for resilient grace—a manifesto for beauty that refuses to perish, even when the pantry is bare.

She writes:

“Probably one of the most private things in the world is an egg before it is broken.”

And in this deceptively simple line lies an entire philosophy of waiting, fragility, and promise.

The Gastronomical Me is, in essence, a female coming-of-age memoir—a voyage of palate and skin—where solitude, desire, and discovery blend into tales of French hotel-room breakfasts, dinners with lovers, and the strange intimacy of eating alone.

In An Alphabet for Gourmets, Fisher allows herself to drift elegantly through letters and memory—a lexicon of the heart, where each entry is a learned and wistful digression. Among the most poignant:

“M for Monastic”, where she celebrates austerity not as deprivation, but as a refined choice. A recognition that restraint is a form of elevated elegance.

She writes:

“The truest gourmet is often the one who loves a crust of bread and a glass of wine more than he does a sumptuous feast.”

And it is to that voice, to that sparse and radiant wisdom, that tomorrow’s recipe will be dedicated—a dish that speaks the language of essentials, infused with quietude and salt, hued like a winter evening, unfolding with the slow rhythm of a secular prayer.

Fisher reminds us that the art of taste is kin to the art of thought, and that taking time to choose ingredients, to arrange them with grace, and to share them with intention is nothing short of radical.

An artist’s gesture, her writing—polished as sea glass, elegant as a hand-engraved menu—teaches us to see the invisible: the soul’s movement in a simmering pot, the pulse of an era in a humble soup, the delicacy of love in a table set for two.

Perhaps that is why reading Fisher often feels like being a guest at a timeless feast—one that stretches across centuries—where each dish is also a story, each glass a secret, and every silence seasoned with words that have been slowly chewed, patiently digested.

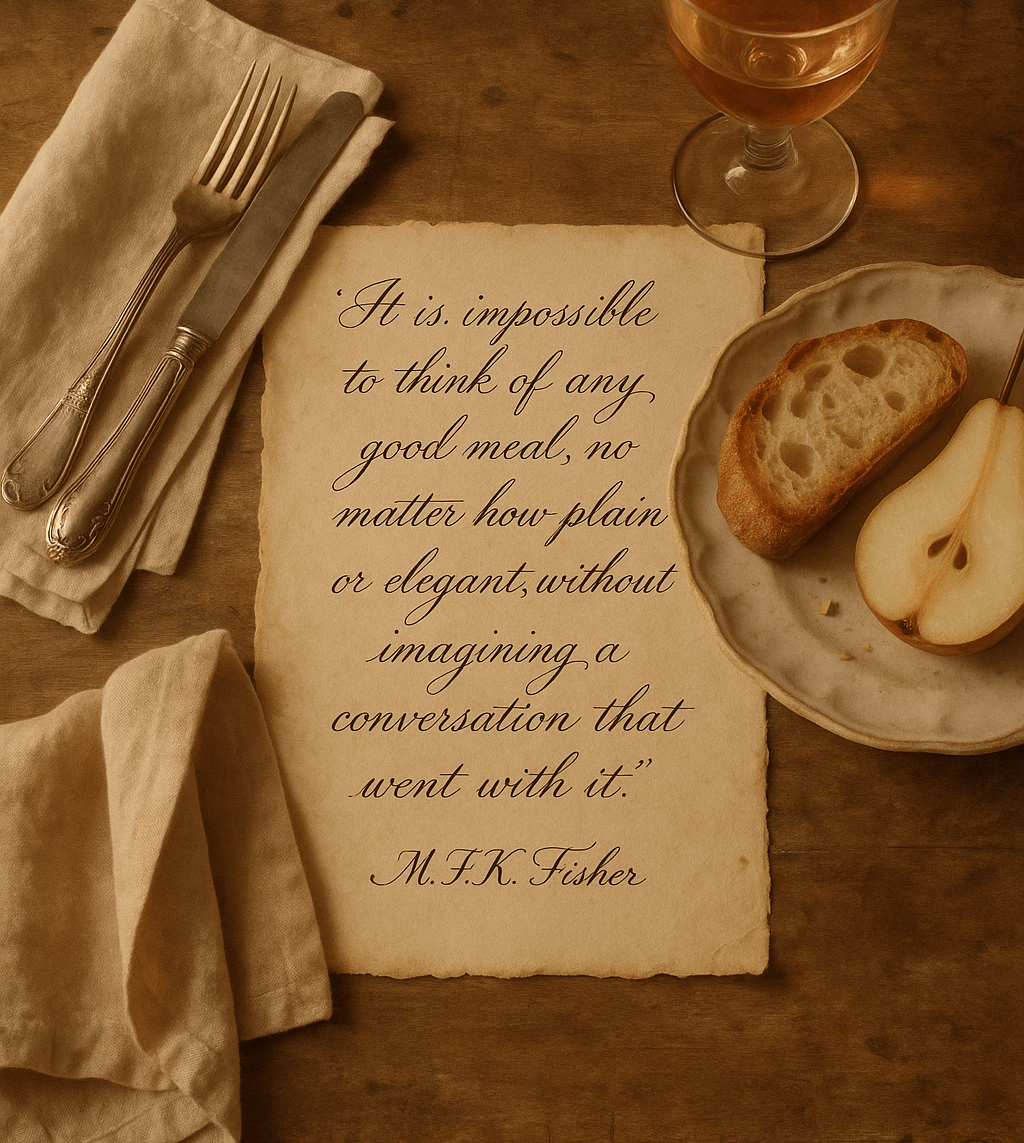

Because (as she once wrote in what may be her most quoted line)

“Sharing food with another human being is an intimate act that should not be indulged in lightly.”

And it is precisely in that intimacy that our deepest humanity resides.

In that tenderness that needs no ornament.

In the warmth of a meal prepared, offered, and loved.

It is there that our being comes back together.

Quietly.

As artists of the everyday.

© Charlotte Madeleine Castelli | All rights reserved