The Eternal Scrap: Marble Conversations with Nazareno Biondo

A journey through the sculptural world of Nazareno Biondo. His works, carved in marble, speak to me like quiet monuments of our time—turning waste, fragility, and forgotten objects into symbols of collective memory. What he sculpts is not just form, but resistance. And through his art, I’ve learned to listen to the silence of stone.

FEATURED ARTIST OF THE WEEK

Charlotte Madeleine CASTELLI

6/18/20253 min read

There is an invisible threshold one crosses when they truly encounter an artist—not in the superficial sense of “meeting,” but in the way one penetrates a world, feels its pulse through the works, listens to its silences.

With Nazareno Biondo, I crossed that threshold slowly, respectfully, like stepping into a room filled with memories and fragilities sculpted into stone.

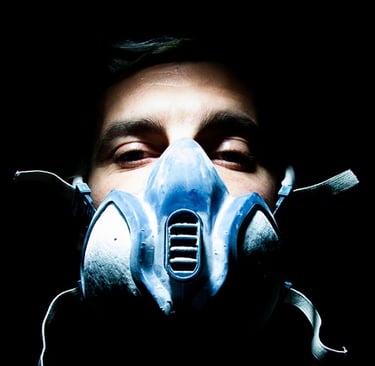

I’ve never been able to look at his works as a mere spectator. They immediately demanded complete involvement. Eyes weren’t enough. I needed lungs, temples, and viscera. Nazareno sculpts our time, but he does so with an ancient grammar, almost liturgical. He chooses marble—the most memory-laden and ideologically charged of materials—to speak about what, in our era, is typically ignored or erased: waste, scraps, the symbols of a society that consumes and consumes itself.

The first time I saw Old Lady, a soft unease took hold of me. There she was—an abandoned Fiat 500 in white marble, like a sacred, wounded body, no longer useful. She was sculpted with an almost cruel precision, as if each scratch on her metal skin had pleaded with the marble to remember. But it wasn’t nostalgia, no… It was a declaration, a silent scream saying: “Look at what we’ve become.”

And I, as curator, as viewer, as citizen of this accelerated present, could do nothing but stop.

I asked myself: can stone become an ethical witness?

Nazareno answered me without words. His art is a language that transcends sculpture. It is philosophy made marble flesh. It is the archaeology of the now. Because his decision to sculpt by hand, slowly, inch by inch, is a profoundly political gesture.

Sculpting is not merely creating. It is subtracting. It is choosing what to leave, what to reveal, what to extract from the mute white mass of marble.

What makes his work so powerful—dare I say, necessary—is precisely that Nazareno doesn’t seek consensus. He does not seduce with beauty. Instead, he exposes us, involves us, forces us to confront what we would rather ignore: cigarette butts, plastic bottles, broken shoes, lost and found objects.

But sculpted in marble. And there lies the short circuit: the most eternal material used to immortalize the ephemeral, the discarded. The artistic gesture becomes a contradiction made form—one that compels thought.

And then there’s Dead of Cuddle. A couple, two bodies lying down, embraced in marble. The loving gesture carved in a cold, indifferent material. But it is not a romantic piece. It is a requiem. There is something funereal in that composition, and at the same time, something deeply human. As if the artist were telling us: even love, in its deepest tenderness, can become discard. Even feelings, if left uncultivated, petrify.

In my curatorial work, I always try to build a bridge between the artwork and the viewer. With Nazareno, this bridge is not built through explanation but through resonance. His sculptures do not seek to be understood, they ask to be listened to.

They speak of a society that produces plastic icons and forgets them, that turns function into fetish, then into trash.

And Nazareno Biondo, with the patience of the ancients, saves them. He fixes them in time. He sculpts them with the same material Michelangelo used to create his heroes and turns them into the new civil monuments of the 21st century.

Curating his work is never just a professional gesture. It is an act of responsibility. Because it means accepting to bring into the heart of the museum—so often sterilized and aseptic—the fractures of the real world. It means welcoming the discarded, elevating it, giving it aesthetic citizenship and narrative dignity.

Technology, in all of this, is not absent. It is witness and ally, not entering Nazareno’s manual act, which remains rigorously analog, carnal, slow,but infiltrating the diffusion, the conversation, the way his works are received, photographed, shared, interpreted online.

Marble, a silent material, finds voice in the language of the network.

And so, a sculpted bottle becomes viral. A marble bottle cap, a banknote, a key—transform into hashtags. A sculpted syringe, relic of human sorrow, travels through worlds and platforms, igniting questions that no AI can truly disarm.

In a time that demands we be fast, flexible, forgettable Nazareno sculpts.

And by sculpting, he resists.

And I, as a curator, remain listening to the stone that speaks.

Post Scriptum

To approach Nazareno Biondo is not merely to meet an artist, but to meet a man, a soul. A vision. A hand that carves marble and a mind that carves into our conscience.

Each work is a dialogue.

Each exhibition, an act of reconciliation between form and time.

The true challenge today is to safeguard that voice and turn it into an echo, so it may never be lost.

© Charlotte Madeleine Castelli | All rights reserved