The Thomas Crown Affair

When art becomes both the object and the stage of desire, theft ceases to be a crime and turns into choreography — a mirror held up to our own obsession with value.

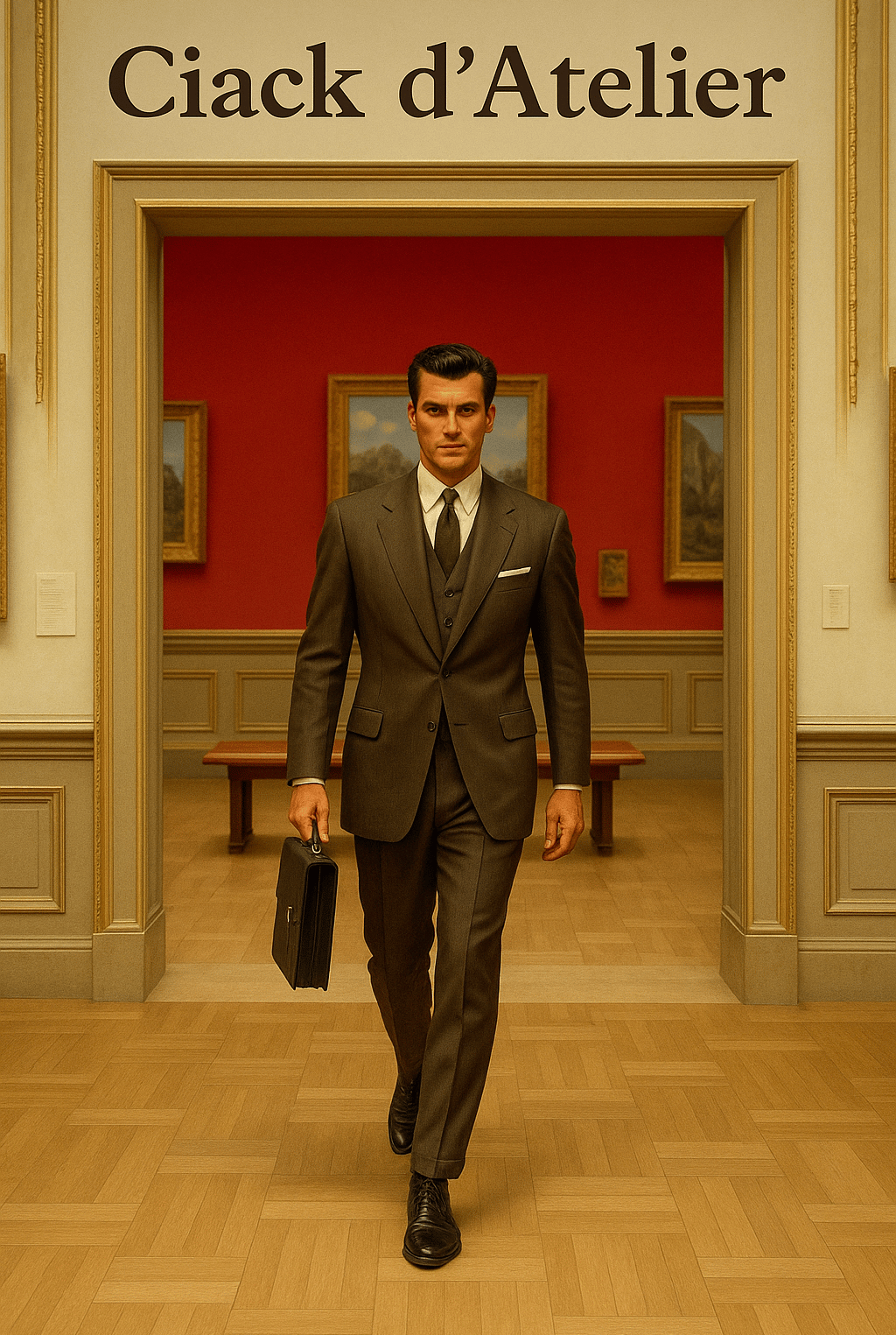

CIACK D'ATELIER

Charlotte Madeleine CASTELLI

10/20/20253 min read

There are moments when cinema anticipates reality, when fiction does not merely imitate life but reveals its hidden architecture. The Thomas Crown Affair (1999), John McTiernan’s exquisitely stylised remake, is one of those rare films where elegance and transgression converge into an act of pure aesthetic intelligence. Thomas Crown, portrayed by Pierce Brosnan with icy composure, steals a Monet not for money but for meaning to reassert control over a world that no longer surprises him. The theft, executed like a ballet of precision and seduction, transforms the museum into a theatre of power: the perfect intersection between eros and intellect, between possession and illusion.

In McTiernan’s vision, the crime is not an act of greed but of authorship. The museum, that sanctum of preservation, becomes the stage upon which Crown composes his masterpiece, an invisible performance in which absence itself becomes art. The replacement of the painting, the multiplication of the thief in Magritte-like silhouettes, the calculated play between reflection and disguise: all converge into a single, vertiginous question: what does it mean to own beauty? The film’s brilliance lies in how it elevates theft to a philosophical gesture, suggesting that the act of stealing an artwork may, paradoxically, reaffirm its transcendence beyond value.

Yet this romantic abstraction collides violently with the reality of what unfolded yesterday at the Louvre in Paris, a heist that has shaken the very notion of cultural security. In broad daylight, thieves penetrated the Galerie d’Apollon and vanished with priceless jewels of Napoleonic and royal provenance, their actions unfolding with cinematic precision, as if McTiernan’s script had bled into the streets of Paris. Reports describe the same cold choreography: power tools, shattered glass, a four-minute escape. The spectacle was not merely criminal; it was performative, an act designed to wound the collective imagination, to remind us that even the most sacred temples of culture are porous.

The resonance between film and reality is uncanny. The Thomas Crown Affair romanticised the solitary genius-thief, a man driven by aesthetics rather than avarice. The Louvre heist, however, exposes the darker mirror image of that myth: the same fascination with invisibility, the same intelligence of disappearance, but devoid of glamour, stripped of poetry, submerged in the opaque mechanics of black markets and capital flows. What unites both is the symbolic violence enacted upon the artwork itself: the reduction of heritage to asset, of aura to collateral.

For curators, collectors, and critics alike, this convergence of fiction and fact is not merely anecdotal: it is diagnostic and reveals the fragility of the ecosystem that frames art as spectacle, investment, and trophy. McTiernan’s film, seen through a curatorial lens, becomes a meditation on institutional vulnerability: the museum as both fortress and façade, its transparency always shadowed by risk. The Louvre theft makes that metaphor literal. The cultural edifice that claims to safeguard meaning has once again become the scene of its erasure.

And yet, within this disturbance lies a paradoxical beauty, the reaffirmation that art’s value does not end where its security fails. Whether fictional or real, each act of theft exposes the tension between visibility and possession, between the image as symbol and the object as capital. To steal an artwork is to rewrite its narrative, to tear it from the chronology of curation and reinsert it into the mythology of disappearance.

In The Thomas Crown Affair, the protagonist escapes, unpunished, untouchable, immortalised in style. In the Louvre, the thieves flee into silence, their triumph measured not in elegance but in loss. Between these two gestures lies the difference between cinema and reality, between aesthetic provocation and historical wound. Yet both leave us with the same unsettling awareness: that art’s most dangerous vulnerability is not the risk of being stolen, but the illusion that it ever truly belongs to anyone.

All rights reserved © Charlotte Madeleine Castelli | Ciack d’Atelier