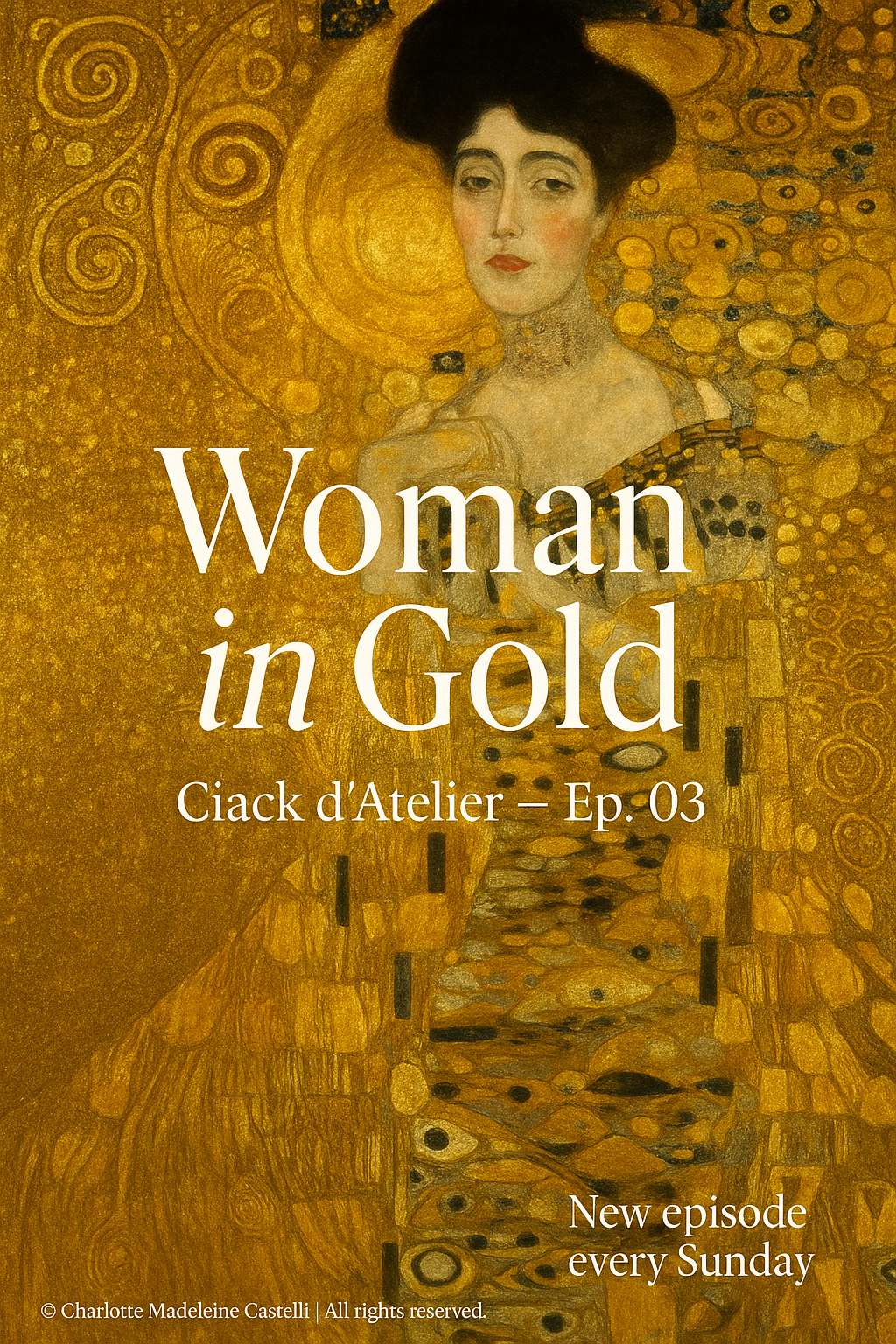

Woman in Gold

In this new episode, I let myself be carried by the golden light of a work that never ceases to question me: Gustav Klimt’s portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer. Through the film Woman in Gold, I retrace the true story of Maria Altmann and her act of restitution as a poetic and necessary gesture. It is an intimate journey—through memory, beauty, and justice—where art becomes a living body, and curatorship becomes the art of listening.

CIACK D'ATELIER

Charlotte Madeleine CASTELLI

6/29/20253 min read

Memory, Justice and Gold: A Poetic Act of Restitution.

"A painting is not merely a work of art. It is a silent witness, an intimate relic, an archive of bodies, memories, and lost identities." cit. © C.M.C., 2025

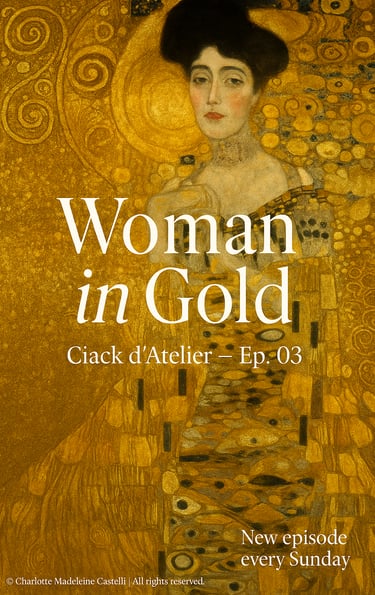

As a curator, I often find myself questioning the silent power of art—its ability to carry the wounds of time without uttering a word. Some works do not remain silent. Some—like beloved people—look back at us, search for us, demand that we answer. The Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I by Gustav Klimt is one of those.

Watching the film "Woman in Gold", I couldn’t help but feel personally called into the narrative—not only because of the evident symbolic and cultural weight of the artwork at its center, but because of how powerfully Simon Curtis' film tells a true story, transforming it into an intimate and universal meditation on memory, justice, and curatorial practice as an act of love.

Maria Altmann—a remarkable woman, both fragile and unyielding—does not simply ask to reclaim a painting stolen from her family by the Nazis. What she demands is far greater: the right to remember, to name what has been erased, to recognize that behind every looted artwork lie faces, rooms, voices, embraces, exiles.

That painting, the woman in gold, is the last tangible trace of her lost Vienna. Looking at it, Maria sees her aunt Adele, her childhood self, family celebrations, intellectual salons, the sound of footsteps fleeing toward the border to escape persecution. In a single image, she sees trauma and beauty layered together, like gold leaf on raw skin.

Gustav Klimt did not paint Adele as a mere model. She was a cultural figure of fin-de-siècle Vienna, an intelligent, complex, magnetic woman. Klimt made her both icon and relic, transforming her into a Byzantine figure suspended between the sacred and the sensual. Her face—realistic, luminous, quietly aching—emerges from a golden vortex of abstract patterns, symbols, and geometries thick with silence.

And then there is that necklace, heavy and refined, encircling Adele’s throat like an ambiguous emblem: adornment or prison? A symbol of status or a mute seal of a society that elevates and enslaves? Some art historians interpret it as a psychic knot, a metaphor for the tension between personal freedom and family destiny. I believe Klimt placed it there precisely for that reason: to suggest contradiction, to trouble the gaze.

In Klimt’s hands, gold is never mere ornament. It is a threshold to eternity, a sacred language, an alphabet of longing and distance. Each of his works is a map of time, and the female body is its temple.

When Maria takes her case to court, the world watches with skepticism. How can a single individual sue a sovereign state? And yet she succeeds. The U.S. Supreme Court, in a historic ruling, sides with her: Austria must return the painting, along with other works taken from her family.

What many don’t know is that this battle was not merely a personal victory. It became a landmark precedent in international law, paving the way for dozens of other restitutions of cultural assets stolen during the Holocaust. But more than that, it reopened an ethical wound at the heart of every museum in the world. Can we truly speak of a “universal heritage” when paintings hang on walls that still belong to someone’s pain?

With a strength that only deep grief can generate, Maria made a rare and powerful choice: after reclaiming the work, she decided to share it with the world. She didn’t hide it. She didn’t sell it immediately. She brought it to America, displayed it to the public, and let it speak. She said:

“It is no longer just mine. Now it speaks for all those who can no longer tell their stories.”

In that moment, I understood her action as not merely political or legal, but rather a poetic act, a pure curatorial gesture—an attempt to mend the irreparable through light, through the gaze, through art itself.

"Woman in Gold" is a film that should be screened in schools, museums, courtrooms. Yes, it speaks of law… but in the language of skin, of memory, of family, of absence. It reminds us that art is a living body: and like all bodies, it can be violated, forgotten, but also returned to its dignity.

As a curator, I know that my task today is not only to exhibit—but to listen. Every artwork is a witness. It is up to us to decide whether to treat it as a commodity or as a threshold to awareness.

And for this, I want to thank the person who brought me to this film. Luca Monaco, affectionately called “Il Magnifico”, a friend, a mentor, a true connoisseur of cinema who knows how to read in images the same veins I seek in pigment. It was he who suggested this film to me, saying: “Charlotte, this film speaks of you.”

He was right.

Because "Woman in Gold" doesn’t just tell Maria Altmann’s story.

It tells the story of all of us... of all those who seek, in art, the path back home.

© Charlotte Madeleine Castelli | All rights reserved