Writing as the Silent Pillar of Curatorship

At La Galleria BPER in Modena, the exhibition The Time of Writing. Images of Knowledge from the Renaissance to the Present Day unfolds as more than a survey of artworks: it is a meditation on the act of writing itself. Curated by Stefania De Vincentis from an idea by Francesca Cappelletti, the show reveals how writing—fragile yet enduring—has shaped the transmission of knowledge across centuries. From Renaissance masterpieces to contemporary interventions by artists such as Sabrina Mezzaqui and Pietro Ruffo, writing emerges not simply as subject but as substance, a living thread binding memory, testimony, and imagination. In this perspective, curatorial writing also comes into focus, not as accessory but as silent architecture of meaning, shaping encounters, weaving narratives, and ensuring that art speaks across time.

TODAY'S HEADLINER

Charlotte Madeleine CASTELLI

9/28/20254 min read

In the contemporary art landscape, curatorship is no longer a mere act of arrangement or cataloguing: it has become a hermeneutic practice, a thought unfolding across space and time, a gesture that translates, interlaces, and rewrites. Within this framework, writing emerges as a crucial presence, not simply a tool of mediation between artwork, artist, and visitor, but as the very substratum of the curatorial act itself. The exhibition “The Time of Writing. Images of Knowledge from the Renaissance to the Present Day”, currently on view at La Galleria BPER in Modena, offers a rare opportunity to reflect on this deeper dimension: writing as both care and knowledge.

To curate, in this sense, is to weave : connections, narratives, and inscriptions across time. The curator does not merely remain behind the scenes: they enter into dialogue with the works through text. Every caption, every essay, every catalogue entry becomes an interpretative act. Each written word stirs orientations, creates silences, opens thresholds. In this way, writing is not a secondary instrument but the very substance of the curatorial project.

At the heart of the Modena exhibition, writing is both theme and object. Works do not only depict “writing” as symbol: they embody it materially, revealing its temporality, fragility, and permanence. Curator Stefania De Vincentis, expanding on an idea by Francesca Cappelletti, conceives of paideia as an active process: not simply inheritance of tradition, but its reinterpretation in the present. Writing, therefore, becomes a practice of renewal, a rhythm through which knowledge re-enters the contemporary.

Genealogy of Writing: Memory and Transformation

Writing is the invention that has wrested time from oblivion. It is breath across centuries, transmitting messages from one generation to another. But to write does not merely mean to preserve: it means to transform, to select, to interpret. From ancient scrolls to Renaissance manuscripts, from inscriptions to conceptual works, writing has played multiple roles: testimony, authority, commentary, ritual.

In the history of art, words and images have always been intertwined: the cartiglio, the motto, the dedication were not secondary additions, but constitutive elements of meaning. With the advent of modern and contemporary practices (photography, conceptual art, digital languages) writing reappears as image, as interference, as material trace. It is not simply about “explaining” the artwork: it becomes an artwork itself.

Behind every exhibition lies writing (captions, wall texts, catalogues, essays). Yet not all writings are equivalent: some expose, some interpret, some provoke debate. The curator as writer is called not to fill voids but to incise trajectories, shaping the interpretative field itself.

Contemporary Curatorial Practice: Writing as Knowledge Production

Recent scholarship in curatorial studies acknowledges that exhibitions generate visual knowledge. The act of writing (whether in didactic texts, essays, or catalogues) articulates the rationale behind spatial and conceptual choices, rendering visible the invisible logic of display.

Writing, in this sense, becomes a form of knowledge production. It is not mere commentary, but co-creation. It structures interpretation, it frames encounters, it opens pathways. Moreover, digital humanities expand this role: curatorial writing now extends into metadata, interactive tags, QR codes, and hypertextual platforms. It is at once rigorous and polyphonic, intimate and public.

Thus, the curatorial text is not neutral. It is a gesture, a voice, a responsibility: to name, to interpret, to create meaning without imprisoning it.

The Time of Writing: Curatorial Choices and Poetics of Display

At La Galleria BPER, the exhibition unfolds not in rigid compartments but as a woven tapestry. It begins with the delicate works of Sabrina Mezzaqui, where writing materialises as embroidery and fragile inscription—an intimate reclaiming of the physicality of words.

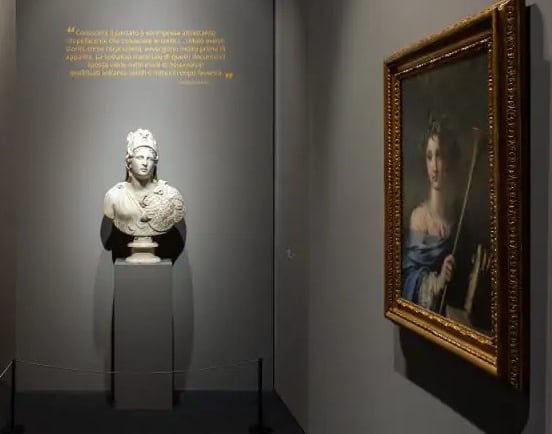

These pieces open into dialogues with masterpieces from the BPER collection and beyond: Giacomo Cavedoni’s The Lament of Jacob, Jean Boulanger’s Clio, Muse of History, the Bust of Minerva from the Galleria Borghese, and Guercino’s Saint Jerome Sealing a Letter from Palazzo Barberini. Each becomes an emblem of writing as testimony, as translation, as shared memory.

The juxtaposition of a seventeenth-century bust of Alexander the Great with Pietro Ruffo’s Six Traitors of Liberty destabilises the authority of philosophical writing, staging the fragility of ideas as pinned insects. Ruffo’s Constellation Globe (2024), presented at the Venice Biennale, extends this reflection skyward: a cartography of stars as ancient writing, always distant, always re-read.

Finally, Alessandro Mazzola’s Madonna and Child offers a symbolic scene of transmission: the Virgin handing a book to the Child becomes the image of knowledge passed on, of writing as legacy.

Writing as Responsibility and Future Horizon

From Modena, a lesson emerges: curatorial writing is responsibility. It is not decorative but constitutive. It carries the duty to name without flattening, to interpret without closing, to offer meaning without dogma.

In an era of textual excess, where words proliferate but meaning thins, curatorial writing must reclaim density, precision, and generosity. It must act as bridge: between expert and neophyte, between past and present, between tradition and innovation.

Above all, writing must remain open, multiform, capable of inhabiting both paper and screen, catalogue and algorithm, silence and voice. It must not simply accompany the exhibition: it must become exhibition.

The Time of Writing in Modena reminds us that to write is to care, to weave, to reimagine. Writing is both memory and possibility, the very medium through which knowledge survives the erosion of centuries. And the curator, in writing, becomes not only mediator but author of shared futures.

© Charlotte Madeleine Castelli | All rights reserved